In conversation with Michelle Good, author, lawyer and voice of wisdom

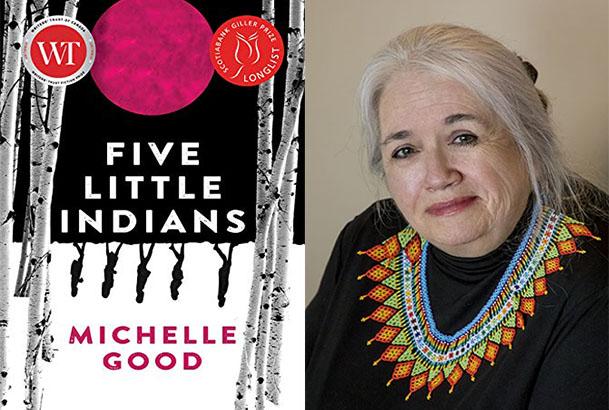

Michelle Good, a Cree writer and lawyer who recently published her debut novel, Five LIttle Indians, will be kicking off her residency at Green College with a lecture on January 19 entitled ‘The Critical Role of Residential Schools in the Colonial Toolkit’. It is the first episode of the J.V. Clyne series she will be overseeing for the year at Green College on the topic of ‘Indigenous Resurgence and Colonial Fingerprints in the 21st Century’.

Good’s novel, Five Little Indians, was longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and shortlisted for the Writer’s Trust Fiction Award. It is a moving and emotionally intense story following the experiences of five characters as they are released from the residential school where they were taken as young children. Cast out into an unfeeling society without family, support or connections, they live with their memories and experiences in different ways.

“I wanted to demonstrate trauma in the world,” Good explained. “Trying to live a life when you’re burdened with traumatic experiences.”

As for the reception it’s received, Good called the response to her novel “amazing.”

“Quite frankly, I thought it would be a niche book, people with a particular interest and so on. It’s just phenomenal, the broad base that it’s reached.”

“At this age, you start thinking you’re in your last act, so it feels really really good to me that something I really needed to say is out there and most importantly that it’s stimulating people to educate themselves.”

With the settlement agreement for the residential school survivors in 2006, there is more information than before in the public domain about what occurred in the schools themselves, Good pointed out. But what she highlights in her novel, and what she said she was pleased was also noted by the Writer’s Trust judges, is that her novel does the much more rare task of articulating the long lasting harms.

“More and more people know about the abuses, but people still are struggling to understand how this can haunt a person's life forever. So that was my objective.”

Good wanted to answer the question that she says “resounds” throughout Canada and is often directed at the descendants and survivors of residential schools: “why can’t they just get over it?”

“I wanted to demonstrate the impact of trauma and when you do that in the context of little children, it helps to illuminate really why this is something that continues to resonate through our communities and through survivors both direct and inter generational.”

Five Little Indians, while entirely fictional, is influenced by the knowledge Good absorbed from the survivors of residential schools she was surrounded by growing up.

“There’s a couple incidents in the book that reflect experiences my mum had when she was just a little kid,” Good said. “There’s a storyline about Clara’s friend Lily who hemorrhages to death from tuberculosis and my mum experienced that. Her friend, whose name was Lily, hemorrhaged to death from TB on the playground with all the kids just watching.”

Good’s own experiences also played a part in her ability to depict the narratives of five youth coming out of an institutional environment.

“I was aging out of foster care, right around the time, chronologically, that these kids in the book were aging out of the residential school. So the same types of challenges, I was facing at the time. Much easier to write that book than the one I’m working on because I lived in that time, I could just resort to my memory as opposed to all the research I’m doing for this book.”

Good is currently working on her second novel, a fictional account of the life of her great-grandmother, a niece of Chief Big Bear. She plans to begin her novel in 1885 with the leadup to the Frog Lake Massacre, an event at which her great-grandmother would have been present due to the involvement of Chief Big Bear’s band.

In the aftermath of Frog Lake, eight Indigenous men were hanged, the largest mass hanging in Canadian history.

“I just want to tell that story through our perspective as opposed to the history books,” Good said. “That’s my goal between now and when I kick the bucket. I want to rewrite history.”

“My mother was a midwife,” Good said. “And she always used to say if anyone knew what is involved in having kids, they wouldn’t have them and it’s the same thing with writing books. You just sort of forget how heinous it was when you were writing the first one.”

If she is forgetfully optimistic about writing a second novel, Good is fully and consciously optimistic about the future of Indigenous people in Canada.

“Hope is really all we have,” she said. “If we abandon hope then where will our energies be fired from? It has to be hope for the future, hope for the coming generations.”

“People say, ‘ah it hasn’t changed’, but I’m old enough, I can tell you it has.”

The focus of the Clyne series this year, Good said will be the things that stand in the way of reconciliation.

“I’ve said this a lot and I’ll keep saying it: I don’t think of reconciliation as peace-making, I think of it in the sense of the bookkeeping term, when you reconcile your bank account with your statement, bringing in the balance. If you think about how much work is necessary to restore a balance in the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada, that’s a huge thing.”

“We can’t have reconciliation without that reckoning, without that understanding that there were mutual promises between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. We don’t get to break our promises because we don’t have the force to throw you out, but that shouldn’t give non-Indigneous Canada permission to break promises again and again.”

Speakers for the series will include John Borrows, a prominent Indigenous legal school who was just named to the Order of Canada, Waubgeshig Rice, author of Moon of the Crusted Snow and a former CBC journalist, and Jessica McDiarmid, author of Highway of Tears.

If, as Good pointed out, all goes according to plan, the first part of the series will focus on the fingerprints of colonialism observable in the 21st century, while the second part, from September onwards, will talk about Indigenous resurgence and how Indigenous people are insisting things must change.

There is adequate material to be gone over in this second part of the series, according to Good.

To truly achieve reconciliation, Good said, requires more change than people in Canada are willing to concede. “People cannot think that life in Canada for non-Indigenous people can go on unchanged and still offer meaningful reconciliation for Indigenous people. There has to be give.”

We are also far away from being able to claim any success in reconciliation, she said, pointing to the continued necessity for boil-water advisories in Indigenous communities and reserves.

“Water, the most fundamental thing in life. How can we talk about reconciliation when we don’t even have water in so many Indigenous communities. How can we take that seriously?”

The problem, she said, may come down to the fact that colonialism left a legacy in Canada of which Indigenous people were not intended to be a part.

“We’re not supposed to be here, we were supposed to have been wiped out and here we are.”

“I think that is the real challenge, that politicians just don’t know what to do because it wasn’t expected that we would survive in spite of all this that we’ve been through and yet here we are.”

Join us on February 23 for the second talk in Michelle's series, titled Treaties: The Terms of Indigenous Permissions with John Borrows, legal scholar and author. You can find all the details to join by clicking here.

by: Jane Willsie, Department of English Language and Literature, UBC; Green College Work Learn Content Writer, 2020-21