– by Mollie Chapman (Green College Society Member)

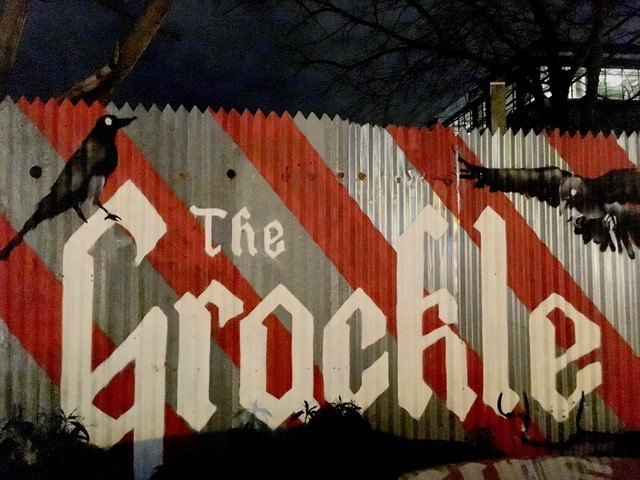

Mural in Austin, Texas depicting the Great-tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus). Photo: Mollie Chapman

What sparks interdisciplinary collaboration? In my experience, these sparks rarely begin in offices or classrooms. The most recent paper we published (see below for a full citation) is no exception. It began when I, an interdisciplinary anthropologist, joined co-authors Alejandra Echeverri and Daniel Karp, ecologists and ornithologists, in Guanacaste, located in northwestern Costa Rica, to share lodging and company for our respective fieldwork projects. I was there to study the intersection of farmers’ values and the Costa Rican Payments for Ecosystem Services program; while Ale and

Danny were studying how rainfall and tree cover gradients impact bird communities in the landscape. Ale, Danny, and I were at the time all members of the CHANS Lab at the Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia (UBC) = Connecting Human And Natural Systems Lab: chanslab.ires.ubc.ca

Over plates of hot tortillas and plátanos maduros (ripe plantains), we discussed the different paradigms of quantitative and qualitative research, the proper translation of “swamp” into Spanish, and the birds that inhabited the forests and farms of Guanacaste. I helped with vegetation surveys and my ecologist colleagues introduced me to local farmers for my interviews. Inspired by my colleagues’ work, I decided to incorporate a section about birds into my farmer interviews. I wanted to understand how farmers related to the natural world around them and a big part of that world involved birds. I worked with co-author and UBC professor Terre Satterfield to craft a set of interview questions that would help us to understand farmers’ relationships to birds. Terre and I realized that sometimes people talk about other species in terms usually used for people, even racialized terms. We decided to ask interviewees about what birds they liked or didn’t like, and also to think about what kind of person or characteristics they associate with particular birds.

I was surprised to discover that my interviewees had mostly positive feelings towards the birds around them—except one. The Great-Tailed Grackle, or “Zanate” (what they call the bird in Central America), was widely disliked, sometimes even despised. It was a nuisance to

agriculture, an occasional threat to small children, and seemed to exhibit what most saw as unethical behaviour by eating the fledglings of other birds. But most curious of all, it was considered to be invasive—a problematic immigrant to Costa Rica’s otherwise splendid natural ecosystems. Yet my ecologist colleagues assured me that this bird was native to Central American mangroves. It was the habitat conversion for agriculture, the increased urbanization, and warmer temperatures that continue to make this species thrive in local towns and in agricultural plots. Ale later surveyed birdwatchers, local urbanites, and more farmers and she continued to find that this species is viewed negatively in this region.

|

Great-tailed Grackles in the parking lot of a super market in Nicoya, Costa Rica. They gather in large groups and according to the locals are loud and annoying. Photo: Daniel Karp.

Back in Vancouver, co-author Ale told this story to Deena Dinat, a PhD candidate in the Department of English Language and Literatures at UBC, over a beer. Deena knew of a parallel case from South Africa. Immigrants were called a derogatory name—makwerekwere—associated with the call of a bird considered a nuisance to agriculture. Deena, Ale and I, are all former Green College Resident Members, and so conversations like this one were not uncommon: living at the College meant that we made friends from all corners of UBC.

Deena brought a compelling theoretical lens to bare on our empirical findings. His interpretation shows how the Grackles become a threat to the nation-state given the Grackles’ perceived Nicaraguan origin. Nicaraguans are often viewed by Costa Ricans as representing a “turbulent political past, dark skin, poverty, and nondemocratic forms of government.” The bird was labelled as a criminal and seen as invading Costa Rican national territories, matching criticisms levelled against Nicaraguan people. Deena called this phenomenon eco-xenophobia, a term originally coined by Ian Rotherham. Given the strong links between political, racial, economic and nationalistic commentaries on the bird, we decided that Deena would be the lead author, as he is a scholar on these topics.

To help us navigate the treacherous waters of interdisciplinary publishing we asked one of our supervisors, Professor Satterfield, to guide us in writing, analyzing and publishing the paper. We eventually found a home for our very unusual study in the journal Human Dimensions of Wildlife. The uniqueness of this paper stems from the fact that we were able to combine critical studies in the humanities and social sciences with ecology and wildlife management. It’s fascinating to see that in one paper we were able to have paragraphs briefly describing the history of the Nicaraguan Civil War, as well as others explaining the diet of the Great-tailed Grackle.

Deena Dinat, Alejandra Echeverri, Mollie Chapman, Daniel S. Karp & Terre Satterfield (2019) Eco-xenophobia among rural populations: the Great-tailed Grackle as a contested species in Guanacaste, Costa Rica, Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 24:4, 332-348, DOI: 10.1080/10871209.2019.1614239

A plot twist to the story is that this species is not seen negatively throughout its range. In fact, in the Colombian Caribbean it is celebrated. Sculptures in five Colombian cities and its presence in local art reinforce the positive image of the bird. According to the costeños (residents of the coast), the Grackle, or as they call it: “Maria Mulata” (also “Cocineras” and “Negritas”) represent their local fauna. Yet, in the Colombian Caribbean island of San Andrés the birds are also seen as “immigrants”, as noted in a newspaper article by Colombian Wayúu anthropologist Weildler Guerra Curvelo [himself a visitor to Green College this year].

|

In Colombian cities like Cartagena de Indias, there are many sculptures and murals that celebrate this bird. Famous Colombian artist Enrique Grau used them in most of his paintings.

|

We are fascinated by this bird and the many reactions it inspires.

Once in a while, drinking beer, coffee, or hanging out with people in other departments yields awesome academic collaborations!

Acknowledgments: Thanks to the farmers and local communities in Costa Rica for sharing their time and stories with us, Grethel Rojas for transcribing interview material, Jim Zook for sharing insights about this bird, and Claude Blanc for fieldwork assistance. Also thanks to our funders: the University of British Columbia, the National Geographic Young Explorers Grant, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for an Insight Grant.

This is an excerpt from the 2018-19 Green College Annual Report. View a copy of the full report here: https://greencollege.ubc.ca/sites/greencollege.ubc.ca/files/2018-19_GCAnnualReport%20WEB_0.pdf